The Grand Old Party is No More

How a once proud internationalist party that championed America’s global leadership has moved into a narrow, nationalist, and nasty direction

Ronald Reagan must be turning in his grave. And John McCain.

The Grand Old Party that led the way for America to lead the world for decades is no more. In its stead is an increasingly narrow, nationalist, and often nasty throng that wants little if anything to do with the world. The exact opposite of what Reagan and McCain stood for.

Reagan was the party’s champion of immigration. The last big immigration reform bill was passed during his administration. And when he gave his final farewell speech from the Oval Office, talking once again of America as a shining city on a hill, Reagan reminded his fellow Americas that in his vision, “if there had to be city walls, the walls had doors and the doors were open to anyone with the will and the heart to get here.”

Compare that to the Republican Senator Pete Ricketts on a panel in Munich this weekend explaining his vote against the Ukraine bill. He told this global audience that the hundreds of thousands of people “with the will and the heart to get here” in search of a better and safer life for them and their families were as big a threat to America as Russian soldiers invading Ukraine and bombing, murdering, and plundering every village and town they came across.

McCain championed America’s security and alliances for decades by leading congressional delegations to the annual Munich Security Conference dedicated to strengthening transatlantic and global security. His presence there was always electrifying, even at his grouchiest moments, and the conference now holds an annual reception in his honor.

For years, McCain brought along his pal Lindsay Graham, one of the “three amigos” (along with Joe Lieberman) to lead the congressional retinue to the Bavarian town at the foothill of the Alps. But two days before this year’s Munich meeting, Graham let it be know he wouldn’t be going. He’d be traveling to the border instead. Why? Because days earlier, after visiting his latest best pal Donald Trump in Mar-a-Lago, Graham had railed and then voted against the bill to aid Ukraine and Israel — both the one with and the one without the stringent border security measures he insisted were necessary.

Graham’s defection from his own, longstanding internationalist stance is the latest manifestation that the Republican Party is now Donald Trump’s party. Even while out of power, Trump’s wish is now the GOP’s command.

Don’t want to fix the border because Trump wants to blame the chaos on Biden? Then let’s vote down the very policy changes we long championed.

Don’t want to aid a Ukraine that is fighting not only for its own but for all our freedom because Trump thinks he can end the war in one day? Let’s not even bring a bill to aid Ukraine up for a vote in the House, and go on a two-week recess instead.

As Ukraine President Volodymyr Zelenskyy sadly pleaded, “please, everyone, remember dictators don’t go on vacation.”

But the party that was once led by the man who called Soviet Russia the “evil empire” destined to end up on “the ash heap of history” and who stood at the Brandenburg gate to loudly proclaim “Please, Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall,” is now led by a man who praises Russia’s murderous president as a “strong leader,” who is “savvy,” “smart,” and a real “genius.”

This narrow, nationalist, nasty view of the world and of America’s constricted role abroad is increasingly dominating the view of the party’s voters and their representatives. As Ron Brownstein points out, nearly every Republican Senator who voted for the Ukraine, Israel, and Taiwan aid package was elected when the party was still led by internationalist leaders like Reagan and the two Bushes. And most who voted against entered office more recently.

Whereas Mitch McConnell, first elected in 1984, championed the aid bill, newly elected Eric Schmitt from Missouri, who voted against, couldn’t wait to replace all the remaining internationalists in his caucus with America Firsters.

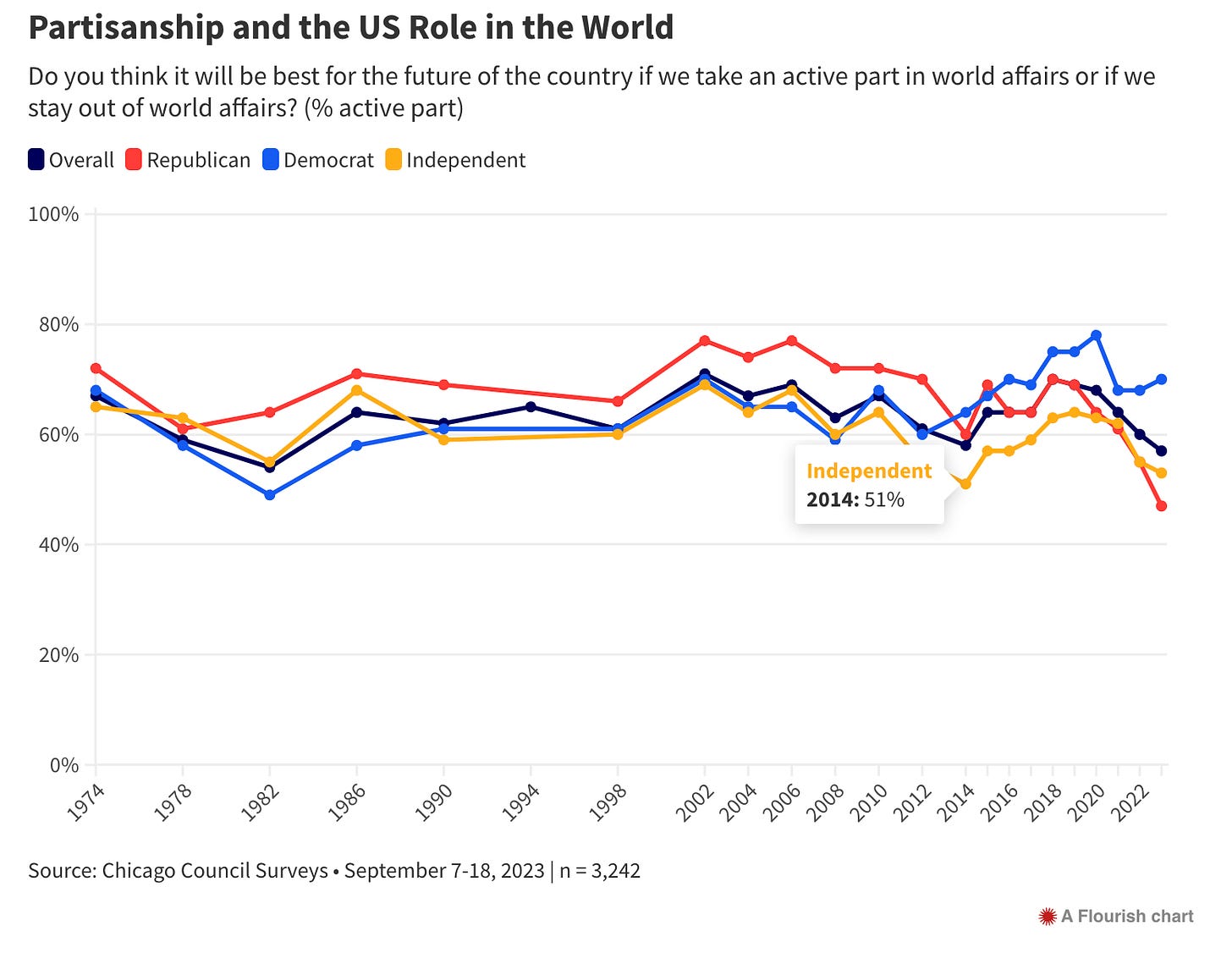

And voters are moving too. As the latest annual survey of the Chicago Council on Global Affairs found, Republican support for the United States playing an active part in world affairs has collapsed. It stood at 70% in 2018 and is down to 47% in 2023. In fact, it as its lowest point in 50 years of polling, and, for the first time, more Republicans think the U.S. should stay out of world affairs than take an active part (47%-53%). With an electorate that is increasingly turning inward, it’s not surprising that a majority of Republican lawmakers are following their voters.

A newly released study of the polling data by the Council, makes clear that this change is predominantly due to Trump’s strongest supporters in the party. The study divided Republican voters between those who had a very favorable view of Trump (47%) and those who had a somewhat or unfavorable view of Trump (53%). While Trump Republicans leaned increasingly isolationist and unilateralist, non-Trump Republican remained more committed to an internationalist course (on a par with independent voters, though far less so than Democrats).

So on the question whether the US should play an active role in world affairs or stay out, just two in five Trump Republicans (40%) favored an active role, compared to an actual majority of non-Trump Republicans (53%)—about what Independents think (though still far less than Democrats).

The same dynamic can be seen when asked about how the US should lead in the world. Overall, Americans far prefer America playing a shared leadership role (66%) rather than a dominant leader role (22%). Democrats, Independents, and non-Trump Republicans also strongly favor a shared leadership role. Not so Trump Republicans, where a large plurality (48%) want the United States to be a dominant leader rather than play a shared leadership role (37%). And almost twice as many Trump Republicans (15%) over non-Trump Republicans favor the US playing no leadership role (8%).

The Council study also explains the divisions within the Republican party in the Senate on the question of aiding Ukraine. Non-Trump Republicans, much like Independents, are far more supportive of sending military and economic aid to Ukraine (59%) than Trump Republican. That is why there is still a large majority of support in both houses for Ukraine (as we saw in the 70-29 Senate vote for aid last week, even though a majority of Republican Senators voted against the package). But the larger Trump looms and the closer we get to November, the more influence he is likely to have over the party as a whole. That is not going to change.

All of this is pointing in the wrong direction. Whereas in his first term, Trump’s narrow nationalist predilections were still checked by a largely internationalist party in Congress and staffing the top positions in his administration, Republicans in Congress are falling in line with Trump and the ever stronger nationalist sentiment among their voters.

Trump is unlike any Republican party leader since the 1930s (remember, Wendell Wilkie ran to FDR’s right on the question of war in 1940). As Jim Lindsay and I have written in The Empty Throne, Trump was the first postwar president not to embrace America’s global leadership role—rejecting security alliances, open markets, and defense of democracy and human rights that have been at the very core of American foreign policy since 1945, supported by presidents of both parties. Trump isn’t interested in leading. He is interested in winning. You lead by getting others to follow. You win by beating everyone else. It’s a fundamentally different approach to engaging the world.

A significant portion of Republicans have now bought into Trump’s approach—some out of conviction, many because they’re along for the ride. And the result is a party that is more and more unlike the party of Reagan and McCain.